It was the morning of September 15, 1963 and a group of young girls were in the basement of the Birmingham 16th Baptist Church preparing for Sunday services. The girls were members of the choir and were getting their choir robes on. The girls were excited about the Sunday service. They made sure they arrived early enough to be ready to sing. The room was full of chatter and giggling. As one girl tied the other’s sash on her dress, the Sunday School phone rang. Carolyn Maull, who was 14 years old, answered the phone. All that was said on the other line was “Three minutes.” and then the caller hung up. Carolyn was so confused but didn’t think much of it.

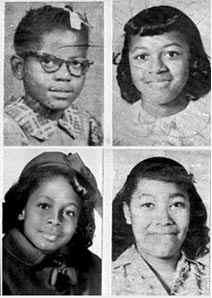

Less than one minute later, an explosion rocked the building. It blew a hole in the wall that was 7 feet wide and left a 5-foot crater. It shattered glass and brick and the blast could be felt two blocks away. A passing car driver was thrown from his car. Dozens of people were injured by the blast and four young girls preparing for singing with the church choir were killed. Addie Mae Collins (14), Cynthia Wesley (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Carol Denise McNair (11)

The explosion didn’t just kill them, it obliterated them. One of the girls was decapitated while another had to be identified by her clothing and ring she would wear on her finger. As rescue workers searched through the rubble, they found the four girls’ bodies stacked on top of each other, almost clinging together.

Within hours, thousands of local African Americans descended on the scene. They were demanding justice. Riots ensued and state police were called to the scene to quell the uproar. Protestors were calling for the arrests of those who set off the blasts. As a result, the Attorney General sent FBI investigators and explosive experts to Birmingham. It was discovered that at least 15 sticks of dynamite with a time-delay detonator were planted under the steps of the church, near the basement.

It became obvious to investigators that this was an act done by the Klu Klux Klan, specifically a subgroup of the KKK called the Cahaba Boys. This group was frustrated by the KKK believing they were becoming restrained in their reactions to desegregation. It was in fact members of the Cahaba Boys: Thomas Blanton Jr., Herman Cash, Robert Chambliss, and Bobby Cherry. The investigations were poorly executed and fraught with racial bias. None of the men were charged for the crime. The case was closed in 1968. Over the years, various prosecutors worked to reopen the case. It wasn’t until 2001 that the last of the suspects were convicted of their crimes.

The 16th Street Baptist Church remained closed for 8 months while it was rebuilt. Donations came from all over the world for both the church and the victims. The events of September 15, 1963 were a major catalyst for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The deaths of those 4 innocent girls started a fire in the hearts of men and women across the country, especially those in the south. It enlivened both segregationists and civil rights activists. It wasn’t uncommon to hear that white segregationists were glad there were now “four fewer n******” in the world. Others had said they were glad the girls were murdered because now they couldn’t reproduce. The hatred and turmoil in the south were thicker than ever after the 16th Street Baptist Church bombings.

In honor of their deaths, President Obama awarded the girls posthumously with the Congressional Gold Medal. Their deaths are a horrible reminder of what hatred can do. Carole, Addie, Cynthia and Carol should still be here. They should have grown up, gone to college, had families, careers and lives full of joy and peace. We all owe it to them to make our world a little less hateful. At Carole Robertson’s funeral, Reverend C.E. Thomas said it perfectly: “The greatest tribute you can pay to Carole is to be calm, be lovely, be kind, be innocent.”